World Fringe Congress Report #4: World Fringe Fair, Open Spaces and Members Only Clubs

Day 3 of the World Fringe Congress began with the World Fringe Fair, a showcase of all the Fringe Festivals present for the general public. We each got a small table, so I set up my infringement materials, including Buffalo Infringement Festival’s 2012 programme, a small booklet explaining the mandate and history of the movement, the ethical sponsorship criteria, and even an article from The Watch about the Halifax Fringe threatening legal action against students at King’s College, Nova Scotia for doing Fringe theatre without permission from the Fringe trademark holders.

On my laptop I offered video viewing of artists being banned and censored at the Montreal Fringe. With my mask from Occupy Montreal and some red squares from the recent unrest in Quebec, I was set to promote the infringement festival to crowds of artists, spectators and producers for the following two hours.

I met all sorts of fascinating people, including politically-charged Free Fringe supporters, such as comedienne Kate Smurthwaite, and even Peter Buckley-Hall, the man behind the widely-admired PBH Free Fringe. He was gentlemanly and edgy at the same time, and when I informed him about the infringement, he was thoroughly delighted.

He told me he might advise someone in Manchester to set one up, raising my hopes that infringement would soon become a permanent feature in Europe. When I asked him if he thought Edinburgh needed an infringement festival, he said that the Free Fringe is already well-known, but after he passes on the reins, who knows? I was thrilled to have met a kindred spirit and a man with a vision and worldview not unlike my own.

Many other artists showed up to my table to chat, such as Behsat Ahmet, who was attempting to do an experimental one-man show at the Fringe, Breathless – A Dramatic Cantata, without losing his shirt. An American artist whose name escapes me, on hearing about Car Stories and the infringement festival, advised me to read Rebecca Novick’s “Please, don’t start a theater company“. Meanwhile many others pitched their shows to me and a woman named Monica Bauer directed me to her article in the Huffington Post, where she wonders why the vast majority of performers at the Edinburgh Fringe had no time for political activities such as showing solidarity with the now-jailed performers of Pussy Riot, arguably one of the edgiest, most Fringe-like groups in the modern age.

All in all, I must have given out infringement information to about 50 different people, raising hopes the movement will continue to spread.

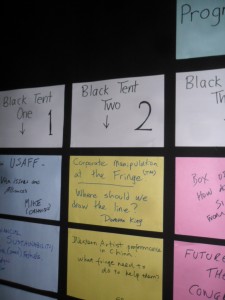

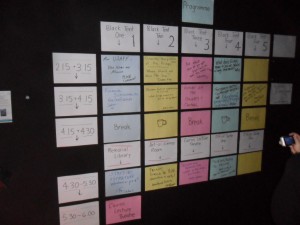

Following the Fair, we rushed back to SummerHall for a series of Open Spaces, a concept explained to us by Paul Levy of FringeReview, a website that reviews Fringe shows. The concept involves participants deciding what they’d like to discuss, then putting it up on a wall. People shop for topics and join the one that interests them the most. If they feel that they might get more out of another topic, they are encouraged to “use their two feet” to move elsewhere, with no offence being taken.

I decided to try and continue the conversation about trying to limit corporate interference at the Fringe, an unpopular topic at the best of times, and wrote: “Corporate manipulation at the Fringe (™): Where should we draw the line?”

A grand total of two people showed up, the lovely Cath Mattos, former Brighton Fringe organizer and current Projects Director of the World Festival Network, and Tim Richardson of the Chelsea Fringe.

I started off by asking for corporate horror stories from their Fringes, but there was concern that if I wrote about sponsors behaving badly it could jeopardize future sponsorships. Despite thinking that this was part of the systemic problem of corporate takeover at the Fringe, I agreed not to publish any names, despite wanting to. One interesting story involved Car Company X sponsoring Fringe Festival Y. Fringe Employee Z, in charge of artist relations, was unable to support the artists because Car Company X demanded all of Employee Z’s time. In fact, Car Company X brought in their cars to showcase and even a slew of their own “street performers”, which seems a bit odd for a Fringe Festival. The main problem was that someone whose main intention was to support artists at the Fringe ended up supporting a corporation instead, most of the time.

Next on the agenda, I discussed the circumstances surrounding the corporate takeover of the Fringe in Canada and the creation of the infringement festival, a story I have repeated many times at this Congress. Slowly, more people drifted into my open space, including Mary McHugh of the Chelsea Fringe, Anneke Jansen of the Amsterdam Fringe and Christabel Anderson, Head of Participant Services at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society.

Next up, I covered the infringement’s Ethical Sponsorship Criteria as a way to prevent the Fringe damaging it’s own brand, then the list of behaviours the infringement festival does not condone:

NO Unethical sponsors

NO Conflict-of-Interest sponsors

NO Visual pollution/corporate spam

NO Pay-to-play fees

NO Box Office “service charges”

NO Trademarking (™)

NO Legal threats for using the word “Fringe”

NO Censorship

NO Kicking artists out

NO Banning political artists

NO Favouritism

NO Security guards/bag searches

NO Hierarchy or corporate structure

NO Naming rights/cross-branding

NO Corporate manipulation/interference

There was definitely no consensus. During the discussion, Tim enjoyed playing Devil’s Advocate on many points. For example, he suggested since all corporations are unethical, we might as well just accept anything that we can find, or that if a small business sponsor uses a vehicle to transport product, it is unethical because the vehicle burns gasoline, which damages the environment. I have heard a lot of these types of fatalistic comments at the Congress, which always lead to the same conclusion: why bother even trying to establish limits when corporate manipulation is inevitable and part of every day society?

What surprised me even more was Anneke’s admission that she had personally kicked an act out of the Amsterdam Fringe for various reasons. As someone who was booted from the Montreal Fringe for critiquing a corporate sponsor, I realized that it is all-too-often arts administrators calling the shots and not the artists themselves at the Fringe. In Canada, with the word “Fringe” trademarked, artists cannot even use it without permission from the Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals (CAFF).

I often worry that booting artists from the Fringe may become commonplace in the future. If artists have no input in the administration, there is nothing stopping Fringes warping themselves into more traditional structures, like the oil-spilling, British-Petroleum-sponsored Edinburgh International Festival

One fascinating point that I learned, which really opened my eyes, is that in Edinburgh an artist cannot be kicked out of the Fringe. Despite the recent criticism that The Fringe is too corporate, there seems to be some confusion about structure. What I realised, after chatting with Christabel Anderson, is that that there appears to be a common misconception about what actually constitutes the Fringe. To be crystal clear: the Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society’s “Fringe” is not actually the same thing as the authentic Fringe.

Christabel Anderson explained that Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society is a service-providing organization that provides services to artists who pay them around 400 pounds; including advice, a place in the program, a central box office, and so forth. Given what appears to be widespread confusion on this issue, I will differentiate the Fringe-proper from the EFFS “Fringe” (whereby artists pay 400 pounds to be included in the EFFS programme and structure).

The actual Fringe is a political and artistic space, not an organization controlled by one group. Anyone can play on the Fringe and therefore it should be impossible actually to kick someone out. The Fringe was originally defined in 1948 when journalist Robert Kemp wrote: “Round the fringe of official Festival drama, there seems to be more private enterprise than before … I am afraid some of us are not going to be at home during the evenings!” The “fringe” is defined as the space surrounding the official festival, both literally and artistically. The initial Fringe succeeded because it created a space where artists could take risks and work on the fringes of everything from the mainstream culture to theatrical hierarchies to artistic perception itself.

Today, in Edinburgh, this authentic Fringe is still there, and its space includes the EFFS “Fringe”, Free Fringes, the Forest Fringe, and artists playing by their own rules, including the infringement festival, incidentally. Internationally, the Fringe space exists whenever artists play on the edge of the mainstream arts. It is crucial that the authentic Fringe never be confused with an organizational structure, such as EFFS or CAFF.

Getting back to our discussion, I concluded by asking if there was any way to get the Fringe Festivals to sign a voluntarily agreement, a mandate that would prevent administrators from selling the the Fringes out to corporate interests. There was little interest in pursuing the issue, so when a bell was rung, our small group moved on to new Open Spaces .

I attended two more circles, including one about the future direction of the World Fringe Congress (they hope to meet every two years) and one run by my edgy kindred spirit, Amy Wragg, about how Fringes should relate to the festivals they appeared alongside. She has set up two Fringes, and prefers to do it without permission or even informing her adversary that there’s a new game in town. We had a good discussion about this dynamic, and this led to the Fringe/infringement schism.

Finally, everyone came into the hall and we all said what we got out of the afternoon. After thanking the delegates for listening to my unpopular message, I repeated it one last time: The more corporate manipulation that exists at a Fringe, the more it loses its edge and extinguishes its spirit. “The Fringe is a delicate brand,” I said, “Please be careful with it.”

Next up was another posh party, this time involving a rooftop reception at Evolution House. While drinking red wine and snacking on savoury duck hors d’oeuvres, Mediterranean pasta and olives, and a delicious mix of field berries with white chocolate shavings, we admired the view of the Edinburgh Castle and surrounding city. Again, while I appreciated the luxurious atmosphere, I couldn’t help but wonder why this was happening at a “Fringe” congress.

I was a bit surprised when a New York Times journalist named Steven McElroy approached me, seeking the scoop on the infringement festival, to which I obliged. Afterwards, I got to meet Kath M Mainland, one of the top dogs at the festival, with the title of “Chief Executive”. While I found her and her staff to be extremely friendly, helpful, and excellent, I felt as though I had been welcomed into some sort of an elite club, certainly nothing like the edgy Edinburgh Fringe I had imagined. To me this felt too posh for the Fringe, and as though to cap off the exquisite party, glorious fireworks began exploding in the night sky.

Our final “official” stop, late night drinks at the fancy “Members Only” Assembly Club, only solidified my thoughts on the subject. To me it seemed that many administrators of the various Fringes, while promoting inclusive open-access in the arts, were also enjoying plenty of exclusive benefits from behind the scenes.

Successful arts administrators tend to enjoy things like respectable salaries, VIP treatment at special clubs, celebrity-access, and, of course, the power and status that goes with it all. In the two-tier world of the corporate Fringes, it seems that while many artists barely get by, administrators are often living it up – in style, no less.

Once outside in the cool night air, the talented Amy Wragg and I decided to do things in true Fringe style. We sat on the steps of an abandoned church on Lauriston Place, mixed a small bottle of vodka into two cans of fizzy lemonade, and proceeded to imbibe.

Feeling much more Fringey than before, we sipped our tasty brews over conversation as we watched the late-night shenanigans unfolding on the street at 3 am, while discussing Fringe and infringement politics. Needless to say, it was yet another late night in Edinburgh.

***

Read more from this series:

Preview: World Fringe Congress to welcome infringement festival

World Fringe Congress Report #1: First Impressions

World Fringe Congress Report #2: The word on the street and Congress opening

World Fringe Congress Report #3: Retaining the Fringe Edge or Show me the Money!

World Fringe Congress Report #4: World Fringe Fair, Open Spaces and Members Only Clubs

World Fringe Congress Report #5: Searching for the Fringe and Reflections