Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation needs support to right a historical wrong

At the northern end of Montreal’s Victoria Bridge, criss-crossed by an urban blight of highways, railway tracks, parking lots, electricity pylons and industrial billboards, lies an old Irish Famine cemetery.

It is a hallowed place in Montreal’s dark history that witnessed tragedy unfold in 1847, as typhus-stricken Irish immigrants disembarked after harrowing conditions at sea in what were known as “coffin ships”. Crowded and disease-ridden, the creaky vessels offered poor access to food and water, resulting in the deaths of many people as they crossed the Atlantic.

The emigrants, many already weakened, were fleeing a devastating Famine in Ireland. While many were quarantined at Grosse Île, north of Quebec City, the medical station was unable to contain the spread of typhus, also known as Ship’s Fever. As the new arrivals continued onward towards Montreal, so did the deadly, infectious disease.

Montreal was unprepared for these desperate arrivals, and fever sheds were hastily constructed at Windmill Point. Religious orders stepped up to care for the sick and dying, despite the dangers of being infected themselves.

An estimated 6,000 people perished from typhus in Montreal, including Irish emigrants and their caregivers. The dead included Catholic nuns and priests, Anglican clergy, and even the heroic Mayor of Montreal. Mayor John Easton Mills, who volunteered to help nurse the sick emigrants in the sheds, contracted typhus himself and died on November 12, 1847.

Most of the victims were interred hastily in unmarked mass graves in a cemetery that was improvised by attendant nuns just to the west of the fever sheds. The Annals of the Grey Nuns (Ancien Journal, volume II, 1847) describes the grim situation:

“Since we had not yet constructed a mortuary for the dead, the corpses were exposed in the outdoors, and once there was a great enough number of them, we made a cemetery for the bodies in the neighbouring fields.”

Today, the only indication of this hallowed ground is a large black boulder squeezed onto a tiny traffic island, straddling two highways, in an unsightly industrial area. Gaudy advertisements on giant billboards glare down on the boulder, which is encircled by a wrought iron fence with a shamrock motif.

It’s known by the local Irish community as the “The Black Rock”, or more officially as the “Irish Commemorative Stone”. It holds a special place in the hearts of Montreal’s Irish community because they had to fight to erect it and protect it.

The Black Rock, made blacker by daily pollution from all the passing vehicles, has an inscription:

“To Preserve from Desecration the Remains of 6000 Immigrants Who died of Ship Fever A.D. 1847-48. This Stone is erected by the Workmen of Messrs. Peto, Brassey and Betts Employed in the Construction of the Victoria Bridge A.D. 1859”.

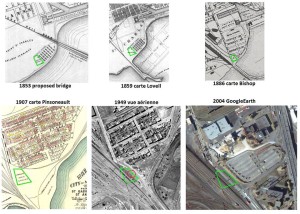

The idea for the monument came about after workers discovered Famine coffins during work on the Victoria Bridge. Not wanting the dead to be forgotten, mostly Irish workers dredged a massive boulder from the bottom of the St. Lawrence River and got to work inscribing it. This makeshift monument was intended to mark the final resting place of the thousands of famine victims in order to remember them and to protect their earthly remains from future desecration.

On December 1, 1859, the Black Rock was erected, becoming the first Canadian monument to mark the Irish Famine.

Historically, the Irish have never had it easy in Canada. After suffering unbearable colonization in Ireland, those who escaped to Canada faced the same colonial masters here – the British. The Irish, as such, were often seen as an underclass to be exploited by Anglo-Protestant industrialists. As the Industrial era set in, many of the survivors and descendants of Irish Famine victims were put to work digging canals, building bridges and working in factories and railyards. The working conditions were often unsafe or deplorable and discrimination and disrespect against the Irish were often rampant.

The site of the Famine cemetery, for example, was administered by the Protestant Anglican Diocese of Montreal, despite most of its victims being Irish Catholics. In 1859, Anglican Bishop Francis Fulford assured that “the bodies of the faithful rest undisturbed until the day of resurrection,” however in 1898 the Anglican Church began negotiations to sell the site to the Grand Trunk Railway, in order to increase the size of its rail yard in Point Saint Charles.

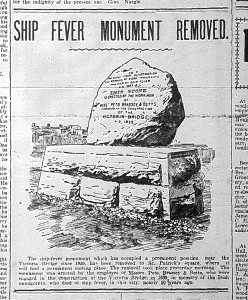

Despite the fact the Black Rock marked the remains of 6000 famine victims, the Grand Trunk Railway wanted it removed in order to expand its operations. To the shock and anger of the Irish community, in the early morning of December 21, 1900, company officials had the Black Rock removed and replaced in Saint Patrick Square to the north.

Angry Irish citizens protested and demanded its immediate return to the site of the Famine cemetery. Matthew Cummings, president of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, expressed the community’s frustration and demanded action:

“A greedy corporation in the city of Montreal dared to lay tracks across the graves… Men of Canada, never rest until it is replaced on the pedestal where it was taken from.”

Despite numerous obstacles thrown up by both the Grand Trunk Railway and Anglican Diocese of Montreal, the Irish community won the battle 10 years later when, in January 1911, the Railway Board of Commissioners in Ottawa ruled that the stone must be returned to the burial site.

However, it also ruled that the Grand Trunk Railway could expropriate the entire site of the burial ground apart from a 30 foot plot of land, fifteen feet from where it originally stood, to facilitate the building of a road. In June, 1912, the cemetery was sold to the G.T.R. for $6,000 and in 1913 the corporation erected a wrought iron fence around the tiny memorial site to try and placate critics.

From that time, the industrial landscape surrounding the tiny plot has continued unabated to develop into an urban eyesore, with railway tracks, highways, electricity pylons, billboards, parking lots and other unsightly developments criss-crossing the cemetery.

The postage stamp sized greenspace marking the cemetery was eventually to become a traffic island in Highway 112, as Bridge Street was expanded to allow easier access to and from the Victoria Bridge.

To ensure the Irish dead are remembered, every year the Irish community organizes a “Commemorative March to the Stone Memorial”. Hundreds of citizens march annually to tiny traffic island on Bridge Street where the Black Stone is located.

As they remember the Irish dead and pay their respects among industrial billboards, heavy traffic belches out fumes while whizzing over the cemetery, while in the nearby yard, rumbling trains roll on tracks built over the dead. Despite these adverse circumstances, Montreal’s Irish community refuses to forget the Famine victims of 1847 or the shabby treatment of their burial ground.

After enduring these trying circumstances for over a century, in 2014, the Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation was formed to right this historical wrong.

“We can’t sit in the middle of the road forever,” said Foundation director, Diana English.

“The time has come to create a commemorative park and pavilion to reintegrate the site into the life of Montreal and at the same time add an important missing link to the history of Montreal, Quebec and Canada.”

The Foundation proposes a cultural memorial-park “to honour these 6,000 immigrants who died; to honour the many French-speaking Quebec families who adopted, and gave homes to, the almost 1,000 children who were orphaned by this tragedy; and to honour the many Montrealers who went out and gave aid to these poor immigrants and caught the fever and died themselves, including John Mills, who was mayor of Montreal at the time.”

Fergus Keyes, a director at the Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation, stated in The Gazette: “On a practical level, a properly designed cultural park, with sports facilities, would provide green space in the rapidly developing Griffintown area. It would make for a much nicer entry to the city of Montreal over the Victoria span. It could perhaps as well be a tourist attraction for the millions of Irish in North America whose ancestors arrived in that 1847 summer and survived.”

Keeping these ideas in mind, the Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation released one proposal for the cultural park that would include a museum, monument, meditation areas and a GAA Irish sports field.

The idea of commemorating the Irish Famine victims of 1847 is not unique to Montreal. Indeed, over the past few decades there has been a general realization across the globe to mark the tragic history of Irish Famine.

There are now over 140 Irish Famine memorials in places as far afield as Ireland, the U.K., Australia, the U.S.A. and Canada.

In Canada, there are elaborate monuments to the Irish in Toronto, Vancouver, Kingston, Quebec City, Saint John, and the largest Famine site outside of Ireland, former quarantine station Grosse-Île. Many of these are protected with historic designations and funding from various governmental bodies.

Ironically, while Montreal has more Irish dead buried than any other location, it is the Irish community, and not government officials, who have protected the historic site over the years as best as possible.

In Toronto, it’s a different story. In 2007, Ireland Park was created under the leadership of Robert Kearns, also a director with Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation. Kearns’ keen interest in commemorating the Irish Famine is also reflected in his other work. He is a featured contributor to a 2009 film entitled Death or Canada, which features Ireland Park and the dark story of 1847 and its impact on the young city of Toronto.

Toronto’s Ireland Park is a world-class Famine Memorial, complete with oak tress, a giant coffin ship made from limestone, a cylinder of stacked glass that serves as a beacon of hope and several bronze sculptures created by renowned Irish sculptor Rowan Gillespie. Located on Éireann Quay at the foot of Bathurst Street, the Toronto sculptures mirror a similar Famine Memorial in Dublin, Ireland, located at the Custom House Quays. Deliberately twinned to create a kind of visual transatlantic narrative, the bronze figures in Dublin represent “The Departure”, while those in Toronto signify “The Arrival”.

It is a fitting and thoughtful Memorial to the Irish Famine, putting Toronto on the map of places around the world that have made efforts to respectfully mark the tragedy of 1847.

In Montreal, the challenges are much bigger, due to the industrial wasteland that has been superimposed upon the Famine cemetery. Canadian National Railways, which absorbed the G.T.R., sold some of the land to the city in 1988, but there are nine other title-holders in the area, including the Anglican Diocese of Montreal. The first step in creating the Irish Memorial Park would be to acquire the property surrounding the stone.

Unfortunately, currently proposed urban plans for the area do not take into account the Irish Famine Cemetery. Opposition party Project Montreal recently released a platform called “Quartier Bonaventure” that would actually authorize the building of residential housing among the grave site.

Once again, it is the Montreal Irish community and their supporters rallying to get the job done properly.

Victor Boyle, the National President of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, announced a $25 million investment towards the creation of the park during the 2014 Walk to the Stone on Bridge Street. Dr. Jason King, an authority on the Irish Famine, also lent his support from Dublin.

Dr. King recently led a project, under the patronage of Ireland’s President Michael D. Higgins, to “digitize and translate the annals of the Grey Nuns who cared for Irish famine emigrants in the fever sheds of Montreal in 1847”. Dr. King ensured these harrowing eyewitness accounts would be available to the public and they are now accessible in a virtual archive hosted by the University of Limerick.

For those closer to home and other supporters, Fergus Keyes encourages people to send an email to Mayor Denis Coderre, “asking him not to approve any plan for light industry around the north side of the Victoria Bridge until this green-space possibility is studied properly.” There is also a facebook group you can join.

To write a letter to Mayor Denis Coderre, please use the City of Montreal’s official website and fill in the form.

Alternately, you can write, fax, or phone him at City Hall:

Montreal City Hall

275 rue Notre-Dame Est

Montréal, QC H2Y 1C6

Telephone: 514-872-3101

Fax: 514-872-4059

A sample letter might look something like this:

***

Dear Mayor Coderre,

I am writing to you today to express my support for the Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation in their plans to establish a world-class Memorial Park for Montreal’s 375th anniversary.

As you may know, there are an estimated 6000 Irish Famine victims buried at the foot of the Victoria Bridge. The Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation proposes that this land be reserved for a world-class Memorial Park, similar to those found in cities like Toronto, Boston, New York, and Dublin. Not only would this plan revitalize an important entrance to Montreal via the Victoria Bridge, but it would also create much-needed greenspace in Griffintown and attract millions of tourists from all over the world.

More importantly, however, it would demonstrate that Montreal is willing to pay respects to its Irish citizens, both historic and present-day. Approximately 40% of Quebeckers have Irish heritage today and the fact that the shamrock occupies a quarter of Montreal’s flag demonstrates our strong historic Irish connection.

In 1847, our heroic Mayor John Easton Mills nursed the contagious emigrants. In the course of his duties, he contracted typhus and perished. It would be a fitting tribute to erect a statue of him in the new park.

As such, I am asking that you set aside the land to ensure it is not encroached upon until a thorough study has been conducted into the feasibility of the project.

Sincerely,

[Your name, address, etc.]